The

diagram at right shows the parts of an artificial drone reed above, and

parts of the vibrating tongue below. The diagram of the tongue shows some

features that may seem unusual if you play Highland or some other types

of bagpipes.

The

diagram at right shows the parts of an artificial drone reed above, and

parts of the vibrating tongue below. The diagram of the tongue shows some

features that may seem unusual if you play Highland or some other types

of bagpipes. The

diagram at right shows the parts of an artificial drone reed above, and

parts of the vibrating tongue below. The diagram of the tongue shows some

features that may seem unusual if you play Highland or some other types

of bagpipes.

The

diagram at right shows the parts of an artificial drone reed above, and

parts of the vibrating tongue below. The diagram of the tongue shows some

features that may seem unusual if you play Highland or some other types

of bagpipes.

The tongue is shown as having two bends, although if you examine a real tongue with magnification, these won't appear as distinct as the diagram and you may not see them distinctly on any but large drone reeds. Uilleann pipers have found that artificial tongues made of flat plastic perform more like cane tongues, and are more stable over the range of variable pressures required by the uilleann chanter, if the tongue bend is created over a distance rather than all at one spot right at the bridle binding.

The diagram also shows an optional weight shown at the free end of the tongue, most commonly used on bass drone reeds. As of this writing I ship all my bass drone reeds with a small piece of cane weight superglued to the end of the tongue because the Daye concert bass drone design appears to require it. I find that it contributes to a "purring" quality in the sound that is well liked by enthusiasts of the narrow bore antiques. In excess it may seem rough or growling. My personal reed actually has two of these for about double the weight. Weight can be added to any of the reeds to increase their loudness and brightness in the blend, or removed to decrease their presence and give a smoother tone.

Over time, a new plastic vibrating tongues can lose a bit of its shape. You may find that it will begin sounding at a pressure much lower than the chanter can play, and it will shut off too easily, before the pressure is high enough for playing upper 2nd octave chanter notes.

The tongue diagram above identifies several important dimensions: the total length of the free vibrating end of the tongue, the short distance between bridle and "stability bend," and the elevation (the amount of permanent rise of the end of the tongue when it is at rest). These dimensions will be different for each different pipe, and there will be some small further variation depending on the strength, loudness and tone quality you desire as your personal preference. As a rule they are all longer for larger reeds and lower musical pitches, and can be very short for the highest pitched drones. Artificial tongues need to be longer if they are made thicker, or shorter if they are made thinner.

For the Daye Concert Drones, the 2 smaller drones seem to take a low resting elevation of only a fraction of a millimeter. The bass however gets its power and deep tone from a significantly higher elevation, 1 to 1.5 mm and possibly more with some combinations of thinning near the binding and weights at the end. This makes the bass reed especially fragile but it is reported to be a way some antique traditional bass drone tongues were finished: loose, high, weighted, and very flexible.

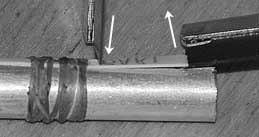

Note:

all adjustments are slight! The photo at right shows a closeup of the

tongue end of a bass reed. You may be able to see a bit of cane weight

glued to the tip end. The dark object in the upper right corner is a razor

blade that is being used to raise the tongue to make the reed louder or

to keep it from shutting off when the chanter plays in the upper 2nd octave.

A razor blade or knife is useful because it reduces the chance of fingers

twisting the plastic tongue. The amount of bend shown is about the most

that will not create a permanent change in the elevation. If the tongue

is lifted much higher, a permanent increase in the elevation will be made.

When adjusting a bass or baritone reed, I recommend that you do not lift

the tongue much higher than the amount shown. The tiny tenor drone tongue

should probably be lifted even less. It is better to repeat a more gentle

lift several times to get the desired increase in strength, than to try

to do it in one higher lift which might create too much bend and therefore

ruin the tongue.

Note:

all adjustments are slight! The photo at right shows a closeup of the

tongue end of a bass reed. You may be able to see a bit of cane weight

glued to the tip end. The dark object in the upper right corner is a razor

blade that is being used to raise the tongue to make the reed louder or

to keep it from shutting off when the chanter plays in the upper 2nd octave.

A razor blade or knife is useful because it reduces the chance of fingers

twisting the plastic tongue. The amount of bend shown is about the most

that will not create a permanent change in the elevation. If the tongue

is lifted much higher, a permanent increase in the elevation will be made.

When adjusting a bass or baritone reed, I recommend that you do not lift

the tongue much higher than the amount shown. The tiny tenor drone tongue

should probably be lifted even less. It is better to repeat a more gentle

lift several times to get the desired increase in strength, than to try

to do it in one higher lift which might create too much bend and therefore

ruin the tongue.

At first, make only the bridle bend as shown in the photo. Adjust the reed with only the bridle-bend to get the desired pitch, strength and stability over the first octave notes. The drone reed should keep playing when the chanter jumps into the lowest note or two of the 2nd octave.

Test the reed for pitch stability. A tuning meter or a matching note sounded from another instrument will be a helpful reference. The common rule for pitch stability is that the pitch change due to increasing pressure tells us which adjustment is needed for the tongue.

At this stage we must cure 100% of any tendency to drop in pitch (going flatter) with an increase in pressure. However, it is acceptable at this stage for the pitch to rise very slightly under increased pressure -- this fault will be fixed with the next adjustment. It is also acceptable at this stage for the reed to shut off when you try to start the drones with the switch valve while the chanter is already playing, or when you try to play the chanter into the middle and upper 2nd octave.

To

increase the strength and stability to allow playing in the 2nd octave,

create the "stability bend." Press a thumbnail down onto the

tongue a short distance ahead of the binding (0.5 to 3 mm, see chart later)

to hold the tongue shut. In the photo, a razor blade is held about 1.5-2

mm from the bridle at left, to demonstrate the position for a baritone

reed stability bend. Then lift the tip several times until there is a modest

new elevation of the tip even when the stability bend location is held

down. It's best to add too little stability bend than too much, because

more lift can easily be added. Removing lift is time-consuming and may

not always work.

To

increase the strength and stability to allow playing in the 2nd octave,

create the "stability bend." Press a thumbnail down onto the

tongue a short distance ahead of the binding (0.5 to 3 mm, see chart later)

to hold the tongue shut. In the photo, a razor blade is held about 1.5-2

mm from the bridle at left, to demonstrate the position for a baritone

reed stability bend. Then lift the tip several times until there is a modest

new elevation of the tip even when the stability bend location is held

down. It's best to add too little stability bend than too much, because

more lift can easily be added. Removing lift is time-consuming and may

not always work.

Tenor Drone Warning: this tiny reed is very sensitive. The stability bend is often needed, but should be very slight and VERY close to the binding. If you're new to making or adjusting double-bend tongues, it's safest to learn on one of the bigger reeds. When holding the tongue down at the mark, the tip elevation should be barely visible, or else the reed will become wild and loud at the lower pressures. For tiny reeds like the uilleann tenor drone reed, use your thumbnail to hold the tongue down, and rest the inside of it against the outermost wrapping of the bridle. Be careful not to move the bridle out of position when you do this.

After

the tongue has been bent upwards at a particular length, the free end cannot

be re-lengthened very much without becoming unsteady and too strong. If

a tongue has been bound shorter and then is a good strength but tuning

too sharp, and/or squeals easily, carefully scraping its top surface over

the 1/8" to ¼" length near the binding will make it more

flexible, similar to lengthening, therefore flatter in pitch and less likely

to squeal or howl. Thinner tongues need to be shorter for the same pitch

and behavior as thicker tongues, so if you accidentally end up with a tongue

that is too short, make it thinner towards the bridle to restore the right

balance of flexibility.

After

the tongue has been bent upwards at a particular length, the free end cannot

be re-lengthened very much without becoming unsteady and too strong. If

a tongue has been bound shorter and then is a good strength but tuning

too sharp, and/or squeals easily, carefully scraping its top surface over

the 1/8" to ¼" length near the binding will make it more

flexible, similar to lengthening, therefore flatter in pitch and less likely

to squeal or howl. Thinner tongues need to be shorter for the same pitch

and behavior as thicker tongues, so if you accidentally end up with a tongue

that is too short, make it thinner towards the bridle to restore the right

balance of flexibility.

If a tongue is lifted too high, you might be able to lower it by binding the entire length of the tongue down onto the body of the reed and letting it sit overnight. Next day, the reed will probably be too easy, and you may be able to start over successfully.

Bottom of the Double-Bend Artificial Drone Reed Page